But they wanted to wait and see just how far prices would fall first. They had billions of dollars standing by - they call it “dry powder,” as in gunpowder - to buy up properties hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. The world’s largest private equity firms like Blackstone had learned a lot after snatching up hundreds of thousands of distressed single-family homes after the last financial crisis. But we knew there were private equity firms circling, because of that exemption from rent control.” “It was perhaps bad timing on the part of the seller,” says Keith Cooley, director of asset management at SFCLT. The building finally came up for sale in early 2020. Nearby San Jose is now exploring a similar law. In San Francisco, COPA has enabled nonprofits like the Mission Economic Development Agency, Chinatown Community Development Center and SFCLT to intercede on behalf of tenants and acquire buildings that otherwise would have gone to market. Until COPA passed, the only place across the country with a similar law was Washington D.C., which passed its Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act back in 1980.

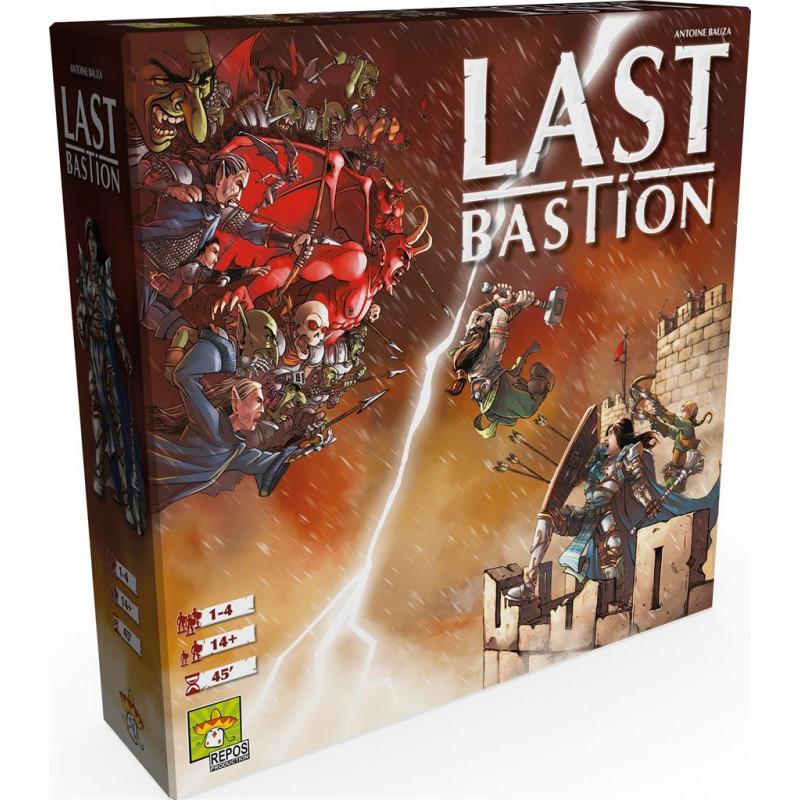

Washington the last bastion affordability crack#

Passed in Spring 2019, the new law gives city-approved nonprofit groups the first crack at buying multifamily buildings when they go up for sale - in efforts to prevent them from falling to the hands of private equity investors or for-profit developers. 285 Turk is subject to San Francisco’s relatively new Community Opportunity to Purchase Act, or COPA. SFCLT set its sights on acquiring the building whenever Mosser finally decided to sell it. In order to sell the building for profit, Mosser needed at least some of that work to get started and higher rent rolls to show the building could eventually pay for the debt taken out to pay for those renovations. More than a handful of units aren’t in good enough condition to rent out at all, let alone justify much higher rents. The building needed - and still needs - plenty of work. One organizer called 285 Turk, “the domino that won’t fall … stopping the whole Tenderloin from being gentrified.” But rents in the building eventually started rising. The tenants were never informed that the building lost its rent-controlled status, which was a shock for everyone to learn in 2017 after San Francisco real estate mogul Neveo Mosser acquired the building and sought immediate rent increases of 5-25%. But in 1985 the city allowed the owner to take it out of rent control after “substantial” investments to rehab the building. A bevy of community-based organizations here serve those households as well as many living on the streets, struggling to hold onto the neighborhood some have called home for decades.īuilt in 1923, a building like 285 Turk would normally be covered by the city’s rent control regulations. The building is 285 Turk Street, at the southeast corner of the intersection with Leavenworth Street, in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood - a last bastion for many low-income households in the city. “All of these things translate into a landscape by which these lenders become more comfortable with us,” says Saki Bailey, executive director at SFCLT. But so did philanthropy, as well as a raft of policies that are slowly shifting the financial landscape in favor of CLTs. The pandemic had something to do with it. SFCLT made this $9.4 million acquisition with zero public dollars and just two private lenders - including a credit union.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)